Clearing for mining

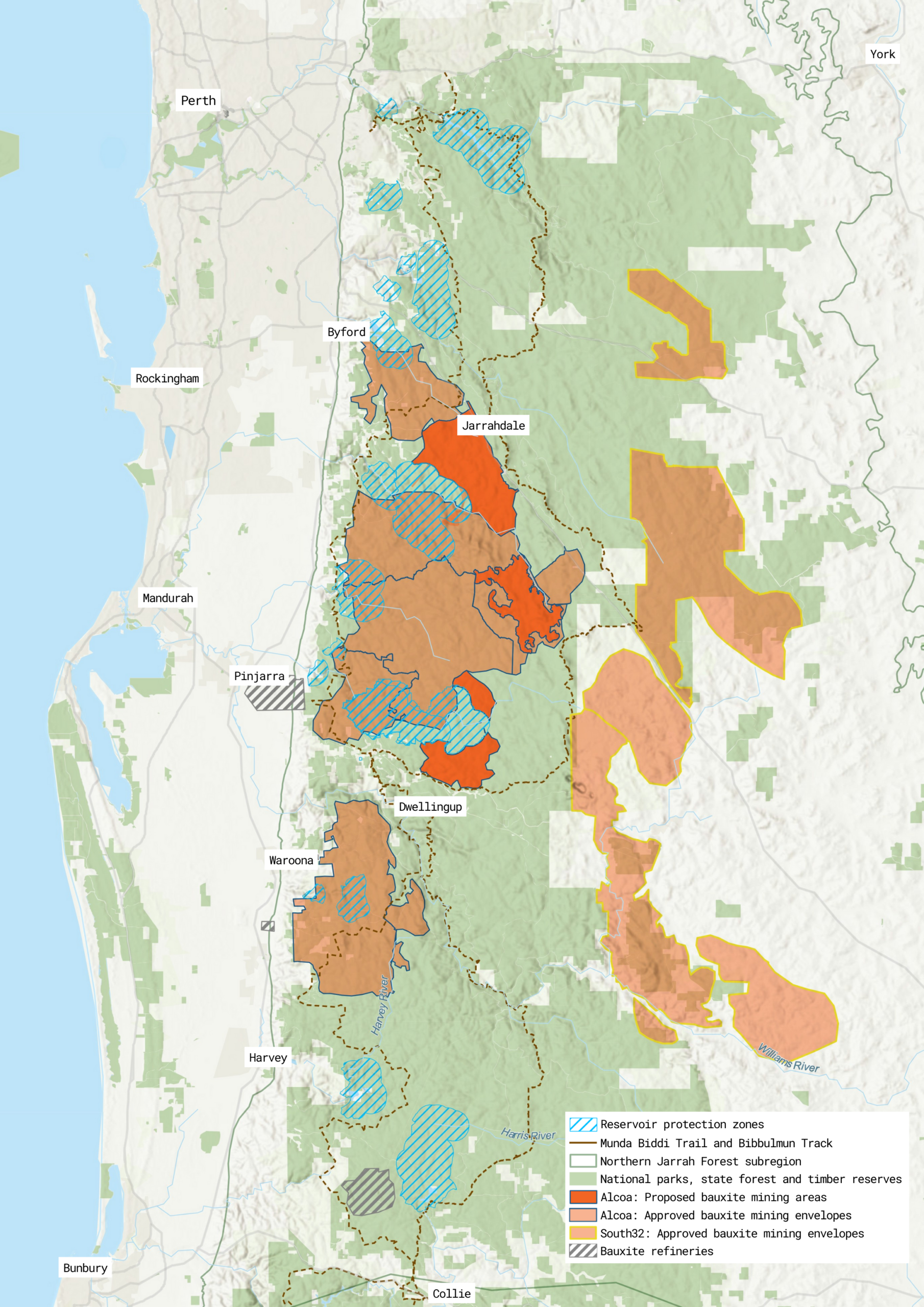

The Northern Jarrah Forest is home to three of the world’s largest bauxite mines. Mining began here in the 1960s, and is now the primary cause of deforestation in the Southwest.

Two major companies, Alcoa and South32, have cleared a combined over 37,000 ha (370 km²) since 1963. Between them, they want to clear another 23,500 ha (235 km²). The rate of clearing for bauxite mining is accelerating, with more than a third of this area cleared between 2010 and 2020.

It is estimated that in the long term up to 83,000 ha (830 km²) will be cleared and 337,000 ha (3370 km²) fragmented for bauxite mining. Most of the forest between Collie and Armadale is expected to be fragmented by 2060.

When bauxite mining occurs, the forest is stripped bare: trees are sold as sawlogs, firewood and charcoal while the remaining vegetation and stumps are bulldozed into heaps and burned.

Seed containing topsoil and about 40 cm of gravel beneath is scraped off and stockpiled. The laterite/bauxite is removed leaving a clay-bottomed pit. Later, this is deep ripped, the topsoil returned and rehabilitation commenced. The topography is forever changed.

Alcoa has consistently maintained that it does not mine in old growth forest. However, the official classification for old growth is narrow and flawed. Many areas of the jarrah forest containing centuries-old trees are not classified as old growth forest due to historical logging.

This loophole means mature ecosystems that provide high quality habitat for diverse species of birds, mammals, frogs, reptiles, fish, and insects are not protected from bauxite mining’s destruction.

Clearing of the Northern Jarrah Forest, 1984-2022 (Google Earth)

A pit created for bauxite mining.

Water contamination and consumption

Bauxite mining presents a serious threat to Western Australia’s vital drinking water sources, with these dangers intensifying as the climate becomes hotter and drier. To safeguard our water supply, we must put an end to all forest mining in our catchment areas.

Rainfall in the Southwest of WA has declined by 20% since the 1970s, and consequently streamflow into Perth’s dams has declined more than 80%, leading to an increased reliance on groundwater, desalination and wastewater treatment for drinking water supplies. Much of this water is stored in dams around Perth, including Serpentine Dam.

All drinking water dams in WA are protected from contamination by a 2 km buffer that bars the general public from hiking, mountain biking, camping, fishing or boating nearby. Despite this, Alcoa is allowed to mine within this area.

Serpentine Dam connects to the Integrated Water Supply Scheme, which supplies water to more than 2 million people in Perth, the Peel region, Goldfields and Agricultural Region, parts of the South West and the Upper Great Southern.

The Water Corporation stated in 2022 that bauxite mining operations represent the single most significant risk to water quality in Perth Metropolitan and South West drinking water catchments. In response to Alcoa’s draft Mining Management Program 2023-2027, it said “Probability of contamination of the reservoirs is considered certain.”

Despite this warning, bauxite mining is still allowed within water catchment areas and within reservoir protection zones, up to 1 km from the edge of dams.

Mining within reservoir protection zones significantly increases the risk of turbidity, where rainfall causes erosion in deforested areas carrying soil into drinking water dams, which can make disinfection processes ineffective. Between 2018 and 2022, Alcoa self-reported an average of 28 turbidity events a year, with this trend increasing over time.

The Water Corporation estimates that the cost of treatment for all dams would be around $3.25 billion (if all intended mining and exploration from Alcoa’s original 2023-2027 Mining Management Program goes ahead). A boil and bottled water advisory would be put in place in the event of contamination, requiring the Water Corporation to supply bottled water to more than 100,000 customers. The scale of the impact could require widespread water restrictions across the entire Integrated Water Supply Scheme.

Per- and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances (PFAS) are a group of thousands of human-made chemicals, known as “forever chemicals” because they don’t break down with time, and build up in the body over a lifetime. Historically, PFAS have been used in firefighting foams, but their use is being phased out.

Alcoa has used PFAS contaminated water for dust suppression, and was found to have built an unapproved pipeline across Samson Brook Dam to move PFAS-contaminated water from its Willowdale mine in 2022. In December 2024, the EPA sent Alcoa a warning letter for what the Water Corporation labelled “an unacceptable risk to drinking water quality.” There were no other consequences for this unapproved construction.

But contamination is not the only risk to Perth’s water that mining carries. Collectively, we estimate that Alcoa and South32 use 48,000,000,000 litres (48 gigalitres) of water a year across their mine sites and refinery operations, drawing from limited groundwater supplies and from dams that should be reserved for drinking.

Explosions close to Serpentine Dam (Jeremy Perey)

A sign at Serpentine Dam. Alcoa’s mining can be seen in the background.

Clean water is vital

As WA’s population grows, and rainfall dwindles, smart water management will be essential for our survival. Continued access to clean, safe drinking water is vital; to allow mining companies to endanger this for short-term gain is reprehensible.

Rehabilitation: Fact or fiction?

Rehabilitation does not grow back the Northern Jarrah after bauxite mining. The research confirms this. It’s time to end mining expansions and protect the remaining forest for life.

For decades, West Australians have been sold the lie that rehabilitation is working, with Alcoa claiming it has rehabilitated 75% of the forest it has mined.

The reality is, this forest has evolved over thousands of years to grow on bauxite. After the bauxite is removed, the forest can never be returned.

Independent scientists have given Alcoa only two out of five stars for its bauxite mine site rehabilitation in the Northern Jarrah Forest, well below what is needed to restore the forest. The Environmental Protection Authority (EPA) states the success of South32’s rehabilitation is “yet to be determined… as evidence of rehabilitation performance have not been provided.”

None of Alcoa or South32’s rehabilitation areas have been signed off by the WA Government as successfully completed in more than 60 years of mining.

Compared to unmined forests, Alcoa’s 20 year old rehabilitation has:

- fewer plant species (less species richness),

- a different species profile (altered species composition),

- fewer functional traits for ecosystem processes (less functional diversity),

- more invasive species (more weeds),

- jarrah trees forking closer to the ground (shrub-like appearance),

- fewer marri trees (important for fauna habitat and ecological resilience).

Moreover, because new growth requires much more water than mature forest, rehabilitation sites deprive nearby mature forests of water, threatening their survival.

Even if rehabilitation did improve, the animals living in this forest cannot wait. Many rely on mature tree hollows for breeding that take more than 100 years to form, meaning that if rehabilitation were to become successful from today, habitat hollows would not form until next century.

Let’s remember, future mine site rehabilitation will occur under very different circumstances, namely a drier and hotter climate that will only make rehabilitation more difficult.

Rehabilitation is not—and never will be—the let-out measure that Alcoa and South32 claim for the significant environmental impact of their bauxite mining. It cannot justify current or future mining approvals.

Offsets: Are they enough?

Recognising their significant impacts on the habitats of threatened animal and bird species, Alcoa and South32 have introduced environmental offsets to “counterbalance” the losses.

International principles of ecological restoration require that compensatory measures not be used to justify the destruction or damaging of existing native ecosystems. In the case of endangered black cockatoos, experts state the remaining high quality habitat is irreplaceable, as even the best offset actions do not regain what is lost.

There is no evidence that any area of offset is an adequate replacement for intact forest areas. The minimal enhancement and protection of fauna habitat created by offset areas simply cannot justify mining expansions that are the primary cause of valuable habitat loss in the jarrah forest.

As is, nesting hollows are scarce, and clearing makes this shortage more severe. Trees with hollows large enough for a cockatoo to nest in may be in the range of 200-500 years old, and there is competition for these hollows from wood ducks, galahs, corellas, feral honey bees, regent parrots, and amongst the three threatened black cockatoo species themselves. Alcoa’s proposal to repair existing hollows will have benefits, but in no way “counterbalance” the massive loss of thousands of future nesting trees lost through clearing.

A large nesting hollow in a Marri tree that has been cut down (Jess Beckerling)

A Carnaby’s Black Cockatoo in a nesting hollow.

Bauxite mining is costing more than just the Northern Jarrah Forest

Bauxite mining in WA operates under outdated State Agreement Acts, legislation that gives Alcoa and South32 long-term access to the forest, and renders them exempt from all laws except work health and safety laws.

The first State Agreement was signed in 1961, by Acting Premier Charles Court, who at the time assured the WA public that only 25ha of forest would be cleared per year. In reality, on average more than 600 ha a year has been cleared since then.

Since 1987, Alcoa and South32 have paid just 1.65% in royalties on alumina exports, the lowest rate in the world. This contributed only 1.3% to the State Government’s revenue from royalties in 2024-25. To put this in perspective: Iron ore—WA’s biggest export—made up 81.4% of all royalties collected by the State Government in 2024-25, and motor vehicle registrations contributed 10.1%, more than 7 times the amount contributed by alumina.

Alcoa’s Kwinana Refinery (Calistemon, CC BY-SA 4.0 via Wikimedia Commons)

Part of the Northern Jarrah Forest that has died due to heat stress and drought (Joe Fontaine)

Under pressure from all sides

Bauxite mining is not the only threat facing the jarrah forest. Clearing for other mining, agriculture and urban development, as well as dieback, prescribed burning, climate change and historic logging, endanger the survival of this ecosystem as we know it.

Alcoa and South32 are not the only culprits of clearing for mining, with companies including Newmont, Telupac and Chalice all wanting their piece. Newmont has an existing mine at Boddington, Telupac has applied for exploration permits, and Chalice has proposed a mine in close proximity to Julimar State Forest.

Alumina refineries are also major greenhouse gas emitters, both using gas, and with South32 also using coal. The South32 Worsley, and Alcoa Pinjarra and Wagerup refineries all make it into WA’s top 10 greenhouse gas polluting facilities. Together, Alcoa and South32 create 8.4 million tonnes of CO2 every year, the 4th and 5th most polluting companies in the state, behind fossil fuel giants Chevron and Woodside, and government-owned electricity and gas retailer Synergy.

Already, the Northern Jarrah Forest is suffering from heat stress and drought. Mature, large trees that provide vital habitat are dying, resulting in forest collapse. Short, multi-stemmed young trees are taking their place, dramatically changing the forest structure and ecosystem values. The risk of further forest collapse and transition can be substantially avoided by halting clearing and the degradation caused by inappropriate management practices and land use.

At the 2021 UN Climate Change Conference COP26, more than 100 countries agreed to end deforestation by 2030 in recognition of the key role native forests play in drawing carbon out of the atmosphere.

For Australia to adhere to its promise, WA must end forest mining.

By bulldozing forests, bauxite mining is fuelling the climate crisis. The Northern Jarrah Forest is key for keeping Perth cool in summer and drawing down carbon from the atmosphere. The more we lose, the worse the climate crisis and its consequences get.