About the Northern Jarrah Forest

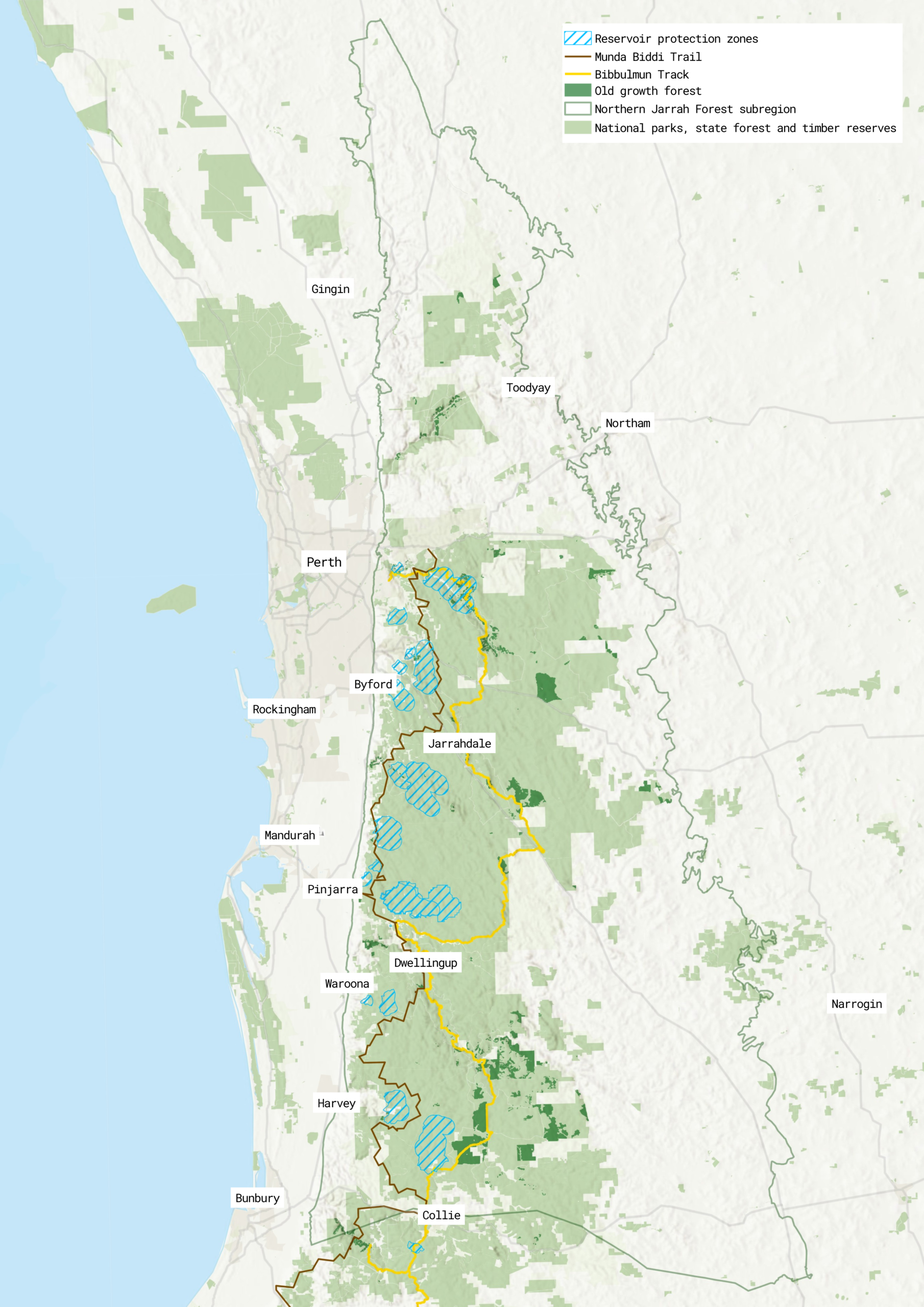

Stretching from north of Toodyay to south of Collie, the Northern Jarrah Forest grows on the Darling Ranges, forming a belt between 30 and 70 km wide, 40 km from the coast of Western Australia.

The Northern Jarrah Forest has evolved over millennia in a delicate balance of climate, water, soils, plants, and animals. It is the world’s most biodiverse temperate forest, and many of the species here exist nowhere else in the world, with plant and animal diversity rivalling tropical rainforests.

More than 780 native plant species grow here. In addition to the dominant jarrah and marri, there are sheoak, banksia, and snottygobbles. Shrubs include grass trees and different types of legumes, protea, myrtles, and wattles. Forming the understory are various types of grass lilies, sedges, orchids, and other wildflowers.

Fungi populations are so diverse that over 100 species have been identified in single study sites.

Importantly, this forest offers high quality habitat for diverse species of birds, mammals, frogs, reptiles, fish and insects, many of them threatened, including black cockatoos, chuditch, quokka, numbat, woylie, and western ringtail possum.

For every one of these species, habitat loss and fragmentation are major contributors to their decline. Further, the recovery plans for each species refer specifically to threats from mining. What remains of their existing habitat needs to be conserved if they are to survive.

A unique biodiversity hotspot

In 2000, the Southwest of Western Australia—including the precious jarrah forest—was declared one of the first biodiversity hotspots in the world and the first biodiversity hotspot in Australia.

This isn’t just a label; it is an urgent warning, telling us that while this irreplaceable region is bursting with unique life, it is also deeply threatened.

A numbat

The Northern Jarrah Forest is home to more than 700 flora species.

First Nations values

The Northern Jarrah Forest always was and always will be Noongar boodja (land). For tens of thousands of years, the Whadjuk, Wilman and Binjareb/Pinjarup Noongar people have been the custodians of this area and its spectacular biodiversity.

There are more than 600 registered Aboriginal sites within the region, including several significant rivers. Noongar people inhabited the jarrah forests in alignment with seasonal changes throughout the year, following the calendar of 6 Noongar seasons: Birak, Bunuru, Djeran, Makuru, Djilba, and Kambarang, which are dictated not by fixed dates but by observations about the landscape and weather.

Traditional ecological knowledge is critical if the jarrah forests are to have a healthy future. These forests must be protected and cared for, and their immense cultural significance must be continually recognised.

How you're connected to the Northern Jarrah Forest

All of us are connected to these forests in some way.

The jarrah forest plays an important role in ensuring Perth and the South West have safe drinking water.

Reservoir protection zones that extend 2 km from the edge of Serpentine Dam, North Dandalup Dam and South Dandalup Dam prevent contamination from bacteria and chemicals by restricting land use. This is why the general public can’t do activities like hiking, mountain biking, camping, fishing or boating within 2 km of a dam. The density of forest surrounding our dams matters too, in stopping water from running too fast into dams and creating turbidity, which can make disinfection processes ineffective.

The jarrah forest keeps the Perth metropolitan area cooler in summer, increasingly important as temperatures climb, and it absorbs carbon from the atmosphere, mitigating some of the effects of climate change.

These forests are home to incredible, world-renowned tracks and trails like the Bibbulmun and Munda-Biddi, frequented by locals and visitors alike. Proximity to Perth makes trail towns like Dwellingup and Jarrahdale popular day and weekend trip destinations for those wanting a quick getaway in the forest.

According to an online survey commissioned by the WA Government in 2021, almost everyone in WA uses the Southwest forests for personal or business purposes, and having access to WA’s native forests is of utmost importance to individuals. Western Australians’ favourite activities to engage in are bushwalking and hiking, bird watching, photography, art, camping, exercise and nature appreciation.

Serpentine Dam, which supplies much of the water for Perth and the Southwest.

A sign for the Bibbulmun Track near Mt Vincent.